Zemfira I. Kalugina

RURAL TRANSFORMATION IN RUSSIA: INCONSISTENCIES AND RESULTS

In Dr.Ieda Osamu, ed., Transformation and Diversification of Rural Societies in Eastern Europe and Russia. Slavic Research Center. Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan, 2002, pp. 41-59

The paper is based on data from sociological surveys, conducted under the author's direction and with her participation in rural Siberia from 1990 to2000, and using statistics and literary sources.

The Situation in the Agrarian Sector and the Conceptions of It's Reformation

Russia has arrived at the end of the century with many of its social problems, including that of food provision, still unsolved. The rate of food product growth in the 1980s was too low to provide for the needs of the national population up to full value and for a balanced nutrition. In a number of areas food distribution was rationed.1 Attempts to improve the situation in the administrative-command system by some shallow adjustments turned out futile in the long run. The underlying reason for this was that social-economic innovations such as intra farm cost-benefit analysis, various types of contract, intensive technologies etc. did not reach the care of the problem. They provided only short-lived improvements and only within specially chosen experimental farms artificially created and enjoying more favourable conditions than elsewhere. After every campaign all things returned to the status quo. The socialist system repulsed those market elements alien to it. For the situation to be reversed radical reforms were needed.1

Radical economic transformation started at the beginning of the 1990s was aimed at constructive changes in the national agrarian sector. It included land reform, reorganisation of collective and state farms - the dominant form of socialist agrarian economy, and the development of autonomous private farms.

The main purpose of land reform was land redistribution between economic agents, equal development of different forms of economic activity, and rational use of lands in Russia's territory. The Land Reform Law passed in December 1990 repudiated state monopoly of land and reinstated the institution of private ownership of land. The right to private land ownership was fixed in the Constitution of the Russian Federation [RF]. But the second (extraordinary) congress of the federal people's deputies in the same year 1990 introduced a 10-year suspension of land sale-purchase; this suspension is still in force despite the decrees issued by the RF President directed at the protection of the citizens' constitutional rights to land and at cancellation of the suspension. The debates on the liberated sale-purchase of farming lands continue.

At the end of December 1991, the RF Government made provisions for reorganisation of collective and state farms and the order of their privatisation. These measures were aimed at changing the organisational-legal status of collective enterprises, giving workers the right to a free choice of a form of entrepreneurship, and endowing them with shares of assets and land along with a right to unchecked exit from the collective enterprise, that is, without the need for the working collective's permit. Reorganisation was to reach every collective enterprise, profitable or unprofitable. On this basis, various partnerships, joint stock companies, agricultural production cooperatives, and privately - run autonomous farms and their associations could be set up. The working collectives were also allowed to maintain - if desired - the parental form of economic activity. Reorganisation was to be completed by the end of 1992.

The development of a privately - run autonomous farm sector began with the adoption in December 1990 of the RF Law "On Autonomous Farms”. This set down the economic, social and legal bases for the organisation and activity of privately-operated farms and their associations as a form of free business run on the principles of economic gain.

In the early 1990s, therefore, was laid down the legislative basis for the formation in the agrarian sector of a mixed economy and for every rural worker's free choice of land management.

Trends in the Agrarian Economy during the Process of Reformation

Reorganisation of Collective Agricultural Enterprises

The reorganisation of collective and state farms had been practically completed by the beginning of 1994 when 95% of collective enterprises were re-registered. In this reorganisation 66% of collective agricultural enterprises changed their organisational-legal status, and 34% exercised their right to retain their parental form. After reorganisation there appeared 300 open joint-stock companies, 11,500 partnerships (of all types), 1,900 agricultural cooperatives, 400 sideline farms of industrial and other institutions, 900 associations of autonomous farms, and 2,300 other forms. The former status was retained by 3,600 state farms and 6,000 collective farms. By forms of ownership, agricultural enterprises were distributed in the following way: state ownership 26.6%, municipal ownership 1.5%, private ownership 66.8%, and mixed ownership 5.1%.2

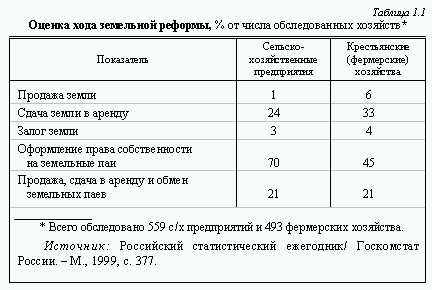

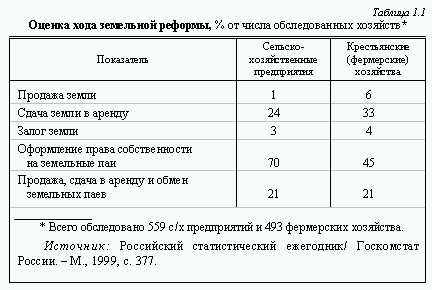

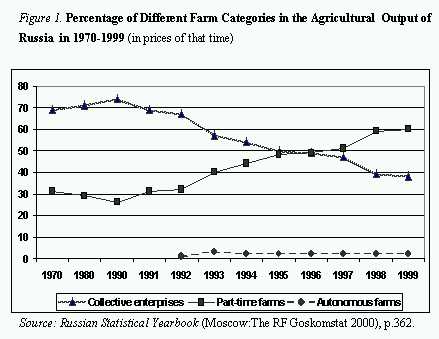

Therefore, the reorganisation of collective enterprises was the first step towards the creation of a mixed agrarian economy based on equality of all forms of ownership and of land management. Unfortunately, no positive results, i.e. better efficiency and higher output, were achieved as a result of this reorganisation. The agricultural output and the share of agricultural enterprises in it are in steady decline. While in 1990 the agricultural enterprises accounted for 73,7% in the total output, in 1999 only 40,3% (Figure 1,2). The positive changes occurred in 1997 and 1999 (Table1).

The number of livestock and their productivity in this category of agricultural enterprises continues to decrease. Most are in a critical economical position.

While at the end of 1991 there was 43% profitability, in 1995 it was minus 2%, and in 1998 minus 28%.3

V. Khlystun, the ex-Minister of Agriculture and Food of the Russian Federation, explains this situation in the Russian agriculture thus: the constantly increasing disparity between the prices of agricultural products and those on material-technical resources used for their production, extremely low state subsidies, low purchase prices, delays in settlement of the accounts for the sold products, monopoly of processing, procurement and service-supplying enterprises and organisations.4

However, in each Russian province can be found some agricultural enterprises, which are successfully functioning under the current unfavourable conditions. A noticeable fact in the activity of such farms is that they have managed to promptly adjust themselves to the new economic conditions: they have studied the market situation, identified the most profitable channels whereby to sell their products, restructured their production according to market requirements, successfully developed the processing of agricultural products, selling them through a network of their own stores, retail markets or trusted wholesale agents at more favourable prices.

Some of these farms have become founders of large commercial structures, and have set up modern agro-industrial companies. They could become centres of scientific-technological progress in the countryside to show other farms how to work under market conditions. But such farms in Russia, by expert estimates, account for no more than 5-7%.

The Development of Privately-run Autonomous Farms

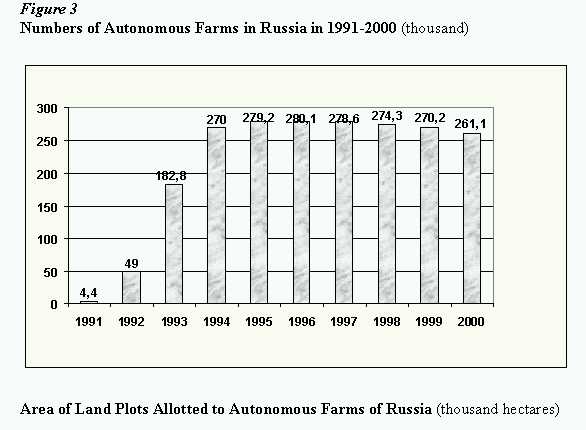

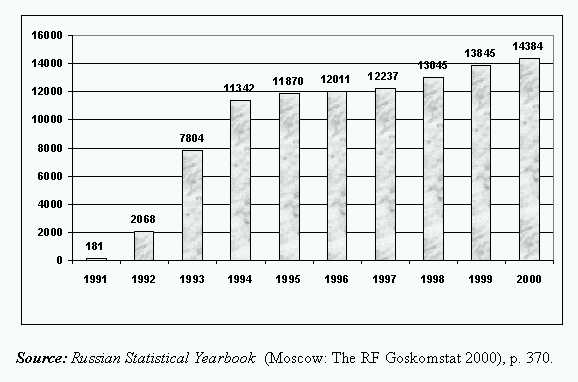

Since the adoption of the federal Law on Autonomous Farms and the reorganization of collective and state farms, Russian peasants have acquired the real possibility of becoming independent economic agents. The dynamics of the number of autonomous farms in Russia show that at the beginning of the reforms the country did possess a social base for the development of the private sector in the agrarian economy. From 1991-2000 the number of privately-run farms increased to 261,000. But by 1994 the growth-rat had began to decrease. And this process of their ruin and surrender is increasing. Since 1997 the number of surrender has for the first time exceeded the number of newly created farms (Figure 3).

The studies conducted in the national regions show that the main causes for instability of autonomous farms in Russia are extremely high taxes, exorbitant prices for agricultural equipment, fuels and other resources, violations of the owner's rights, low subsidies from the state, allotment of lands of low quality and distanced from inner regions and the lack of roads and communications.

We realise that a part of the failure must be attributed to subjective causes, to the Russian peasants' lack of experience in independent economic activity, lack of knowledge, and an unpreparedness to work under economic and social risk.

Agricultural lands in autonomous farms occupy 15.5 million ha (94% of allotted lands), including 10.4 million ha of arable lands (72% of allotted lands). Autonomous farms accounted for 5.3% of agricultural lands and 6.3% of arable lands. Over a half of autonomous farms had 20 ha or less, and a fifth 21-50 ha apiece; no more than 9% of autonomous farms had over 100 ha apiece.5

The proportion of autonomous farms in the total agricultural output is steadily low and does not exceed 2-3%.

Back in 1991, when analysing the necessary and real conditions for the development of autonomous farms in the country, we arrived at a conclusion that blanket de-collectivisation was too rash. Considering the state of the public mind, the level of industrial potential, the condition of legislation, the features of the social-political situation in the country, and taking into account that for transition to a market economy much time was needed, we came to the conclusion that in the foreseeable future autonomous farms could not become a dominant form of agricultural production in the Russian countryside. It was possible to speak only confidence about existing preconditions for the establishment of a mixed agrarian economy, where autonomous farms would be one of its sectors.6 These predictions were fulfilled.

The proportion of autonomous farms in the total agricultural output is steadily low and does not exceed 2-3%.

Back in 1991, when analysing the necessary and real conditions for the development of autonomous farms in the country, we arrived at a conclusion that blanket de-collectivisation was too rash. Considering the state of the public mind, the level of industrial potential, the condition of legislation, the features of the social-political situation in the country, and taking into account that for transition to a market economy much time was needed, we came to the conclusion that in the foreseeable future autonomous farms could not become a dominant form of agricultural production in the Russian countryside. It was possible to speak only confidence about existing preconditions for the establishment of a mixed agrarian economy, where autonomous farms would be one of its sectors.6 These predictions were fulfilled

Development of Part-time (Household) Farming of Rural People

Part-time farming (PTF) is a specific segment of the agrarian economy based on the use of resources and the labour potential of rural families. Part-time farms as a special form of production under socialism had appeared by the end of the 1920s in the process of socialisation of individual peasant farms, and was based on state ownership of means of production, including land, and on the personal (not hired) labour of the plot's owners and family members. In 1991 the household plots used in part-time farming were, under the Constitution of the Russian Federation, passed over to citizen ownership. As a rule, the part-time farm is a sphere of secondary employment existing along side primary employment in the public sector of agriculture.

In the process of agrarian transformation and partial disintegration of collective farming, the protracted and complicated character of the establishment of new economic forms in the agro-industrial complex, the role of part-time farming as the most flexible, steady - enough and self-tuning organisational-legal form in the agricultural production has increased.

While in the public sector there has been a notable decline of agricultural output, in the households' part-time farms, on the contrary, it was increasing to make up in 1999 57% of the total national output.

According to statistics, in 1998 16.6 million families in Russia had household plots with a total area of 6.4 million ha, or 0.40 ha per household. In addition, 14.5 million households had land plots in collective gardens with a total area of 1.3 million ha or 0.09 ha per household. The collective kitchen gardens with a total area of 0.45 million ha are used by 5.1 million households, or 0.087 ha per household. And 6.1million households keep large cattle, 4.1 million have pigs, 3.0 million households keep sheep and goats. As of 1 January 2000, households hold 10.1 million head of large cattle, 7.8 pigs and 9.1 sheep and goats combined.7

In 1994, 1997, 1998, however, there was a stabilisation or even reduction in the output of agricultural products on part-time farms (Table 1). In our view, the emergent trend to a certain decline in the households' output is attributable to several reasons. One is a consequence of the destruction of the production potential of collective enterprises the resources of which (fodder, seeds, agricultural equipment, transport vehicles etc.) have been used by household farms under privileged conditions. The second point is that the financial possibilities of a rural family have substantially diminished, with the result of a lowered standard of living, including depreciation of savings. Point three is that the labour potential of a rural family has practically been exhausted. Analysis of the time budgets of the rural population has shown that many families are running their part-time farms to the limit of their physical power.

At present, legislative and economic prerequisites have been created for the development of the part-time farm as an equal form of agricultural production and for its possible transformation into an autonomous farm.

First, the legislation has fixed the equality of all forms of agricultural production, recognising the part-time farms of households as a rightful form of economy in the agrarian sector. And all work collectives and individuals are granted the right to choose a preferable form of production in accordance with their wishes, opportunities and needs.

Second, all constraints on the number of animals held by a household have been removed.

Third, according to the current legislation, household land plots can be enhanced up to one ha by lands that are in the management of local councils. Apart from this, rural inhabitants who were granted land shares (workers of agriculture, pensioners, and some categories of workers of the social sphere) are entitled to use them for extension of their part-time farms.

And, lastly, according to the operative federal Constitution, land and other means of production can be privately owned.

Under these conditions rural households have a choice: either to run their part-time farms in cooperation with other economic agents of the agro-industrial business with the aid of collective enterprises, or to transform PTF into autonomous farms. The possibility of such a transformation is recognised by about 20% of rural respondents. The base for transformation of some PTFs into autonomous farms could be a large PTF of a commodity type to which about a fourth of rural families are oriented. But over a half of the rural families surveyed think it impossible to transform the PTF to an autonomous farm because, according to them, PTFs cannot do without aid from collective farms. The latter, even under difficult economic conditions, continue to give their workers different kinds of aid in the form of young animals, seeds, agricultural equipment and transport vehicles under privileged conditions or free of charge.

According to the assessments by experts (professional and administration workers of agriculture; the number of respondents is 566), the prospects of PTF transformation into autonomous farms are more pessimistic. No more than 2.9% of experts believe that PTF can be viewed as a transition to the autonomous private farm, while 61.2% believe that PTF can be successfully developed only in cooperation with collective enterprises.

In our view, the perpetuation of PTFs in their former type is promoted by the existing order of taxation where household plots are practically exempt from income taxation because the land tax paid by PTF, due to its small amount, does not affect their profitability which is further substantially increased through the use (free or under privileged conditions) of the resources of collective enterprises. Such a position of PTF as a specific form of non-official agrarian economy is understood by most of the rural population and is reflected in their behaviour. Rural people understand that the transformation of PTF from the non-formal sector of the economy to the formal one will involve a very hard tax pressure and cease of aid from collective enterprises.

The role of PTF in the process of an establishment of private sector in the agrarian economy is contradictory. Being developed in parallel with and, substantially, at the expense of resources and aid from collective enterprises, if perpetuated it would preserve the old system of economic relations. But, on the other hand, it helps the rural people to acquire skills of frugal and efficient management of land, and develops in them the social qualities required in a market economy such as business-like character, entrepreneurship, and independence. The characteristic features of PTF operators and their families are freedom of activity, independence in economic decision-making, and full economic responsibility for the results of their work. In other words, private part-time plots help shape economic agents of a new type.

Although at present most rural inhabitants do not dare to undertake the operation of an autonomous farm, current realities (decline of production in the public sector, very low wages in agriculture, irregular payments, increasing unemployment) enforce them to expand the scale and commodity quality of their part-time farms which, by scale and function, are approaching the autonomous farms. And the former collective and state farmers are, as if involuntarily, becoming autonomous farmers.

So far, the latent processes going on in the contemporary Russian countryside have remained beyond the comprehension of the public, and thus need to be thoroughly researched. It is these processes, in our view, which can mould the trends and character of changes in the Russian countryside in the near- and mid-run.

On balance, the following can be noted. If judged by formal indicators, the planned transformations have achieved a certain purpose, i.e. the number of collective and state farms have been reduced, and signs of a mixed economy and diverse ownership forms have appeared. But what is the merit of these transformations and what is their social price?

Here follow some illustrations.

By estimates of the Russian Agricultural Academy, as a result of the transformations conducted in the countryside, Russia was thrown back by the number of head of large cattle - over a quarter of a century; by animal productivity 25-30 years; by technical equipment - almost half a century. Capital investments in the agro-industrial business diminished 20 times over. During the period of the reforms implementation, the living level of both urban and rural population sharply declined, as did the consumption of staple foods. When compared to 1985, per capita meat and meat product consumption fell by 15%, milk and milk products, eggs by about 20%, sugar and vegetables - by over 30%, oil - by 40%, fish - by about 60%. An increase was observed only in the consumption of potatoes and baked products.8 In the provision of food products, Russia receded from the seventh to the fortieth position among the advanced nations of the world. According to the RF Goskomstat data, in 1995 54% of foods consumed by households were imported using external loans for payment. By estimate, in 1995 the average statistical citizen consumed 2300 calories per day - yet, taking into account the natural climate conditions, he needs no less than 3200 calories. Malnutrition, among other factors, was negatively reflected in the state of health of the population, the death rate, and longevity of life.9 The last dropped from 68 years of age in 1990 to 62 in 1996. 10

Paradoxes of the Agrarian Reform

The dynamics in the development of the three segments of the agrarian economy clearly shows the first paradox of the agrarian reform, namely the expansion of small commodity production. Contrary to the reformers' intentions, the leading sectors of agricultural production are now not autonomous farms or joint stock companies but part-time farms of rural dwellers. They have no means of mechanisation, partly because of the tight market for small equipment suitable for use on private plots, but mostly because of lack of the resources for their purchase of this. The doubled production output and commerciality of this category of farm was due only to the higher labour inputs made by their owners and members of their families. But the expansion of small commodity production has many shortcomings - the economy becomes naturalised, returns to barter, the technological level of production declines, requirements of agrarian technology are not met, and environmental problems appear.

The second paradox in the current agrarian transformations is inefficiency of agrarian economy "capitalisation". The policy-makers themselves have had to admit that in place of a non-efficient state sector of the economy, after reformation they got a non-efficient private sector. In our view, the underlying cause was the formal character of the transformations. The organisation-legal status of collective and state farms was changed but, in essence, economic relations remained the same. The position of workers in the system of relations of production has for all practical purposes remained unchanged.

As most workers have never felt any difference between their previous state as employed workers and their present one as co-owners, no distinct change has occurred in their work motivation or behavioural pattern. In the federal President's message to the Federal Assembly of 1997 it was noted that "the established mutual rights and responsibilities between the owners (stockholders) and managers (directors) were not observed. Directors often merely pushed the stockholders, even major ones, aside from making important decisions in matters that were exactly in owners' competence". According to this, protection of stockholders' rights, clear definition of rights and responsibilities of stockholders and managers, and perfection of the mechanism of corporate management were determined as priority tasks for the Government on which the course of the reform in 1997 depended.

The economic mechanism by which peasants can exercise their rights of ownership to their shares of land and other assets is not yet in operation. As was found in our surveys of the Novosibirsk oblast, over 80% of the respondents had had no dividends on their shares of asset and land, which they had handed over for the use of agricultural enterprises. Most enterprises are at a pinch, unable to pay dividends to their workers. This situation is also typical of other regions of the country.

The third paradox of the reforms is that, instead of developing in people market mentality and behaviour in the sphere of economy, they are in fact destroying their work motivation. And the most vivid of these consequences is seen in the agrarian sphere with its gap between workers' orientation at higher earnings and the depleting possibilities of agricultural enterprises to reward their contribution. As things stand today, the wages of agricultural workers are the national lowest, being less than 40% of the national average; they are below subsistence level and they are systematically paid several and even further months back. Apart from this, the fair relationship between work remunerations and workers' contribution and their qualifications have been destructed.

One third of rural workers said that the size of their remuneration was not contingent on their enterprise efficiency. Employment in the public sector has now ceased to be a primary source of income for rural workers. According to data from the 1997 survey (number of respondents - 553) of the rural population, only 38% of respondents said that their wage was their primary source of livelihood (monetary and natural); 42% said their household farm provided the primary source.

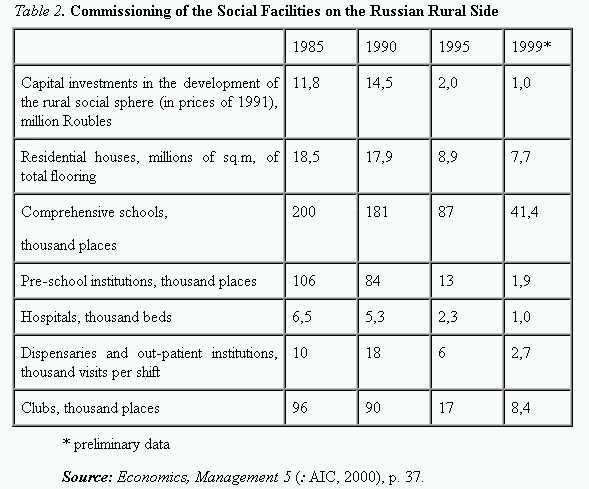

Apart from this, the possibility of agricultural enterprises to solve social problems of the workers by their own resources and means has drastically decreased. Before reformation a job-contingent principle in the distribution of many social satisfactions prevailed. From his enterprise a worker could get free housing, places in a pre-school institution for his children, medical treatment, partially or fully free accommodation in a health resort, and other social benefits. After reorganisation, the collective and state farms were allowed to pass over the management of establishments of social and cultural services to local governments, which in their turn, lacked the sufficient financial resources and an appropriate material-technological basis. This led to a substantial worsening of social services provision in the countryside.

These processes are at the core of a sharply decreased motivation to professional, high-quality and effective work as well as being responsible for the drastic drop in the prestige of work in the public sector, especially among rural youth. According to the 1997 survey, 31.9% of rural inhabitants would like to not work at all, if unemployment relief could provide for a fairly well-to-do way of life (replies of the type; "yes", "rather yes than no"). However, only three years back (in 1993, 525 respondents) such answers to this item were given by no more than 10.6% of rural respondents. In our view, this is a very alarming symptom.

The destruction of the effective system of work remuneration has also been reflected in the attitudes in the sphere of work held by different social groups. Thus, over a half (65.8%) of the respondents preferred to have albeit a small but guaranteed income. Only 28.9% of the surveyed were not averse to high risk in exchange for high earnings. This situation makes people, on the one hand, gradually lose their self-confidence and, on the other, become used to state paternalism.

In other words, the emerging institutional space and the operating economic mechanism work at distorting the system of individual values, decreasing or bringing to nothing the instrumental value of work in the public sector of agrarian production, promoting more social infantilism than developing market behaviour and mentality, stripping transformation in the agrarian sector of its social base and hindering the process of its modernisation.

And, finally, the fourth paradox is that the social result of all transformations in the agrarian sector was utter poverty of the rural population, a degradation of the rural social sphere caused - to a high degree - by its being passed from the books of the agricultural enterprises to the books of local Councils. The latter have neither financial nor material technical resources for the maintaining and development of social-consumer facilities (Table 2).

The social price that has had to be paid for reforms has led to people's disappointment and a loss of confidence in their own wisdom. The consequence is an increasing nostalgia for the past, for the former life, for socialism. According to recent sociological surveys of rural residents, over 60% of the respondents said that their expectations for the situation to improve through the reforms had not been met, 20% that they had been met partially, and only a tenth said that they had been fully met.

Underlying Causes and Possible Ways Out of the Impasse

Underlying Causes

The chosen model of agrarian relations imposed from the top failed to take into account the traditions and historical experience of agricultural production, as well as the collective-individual character of the development of agrarian relations in Russia.

A disregard was shown for the value preferences of the rural population, most of which continue to be oriented to collective forms of economic activity, corporate solidarity, and the state form of ownership. In consequence, the principal ideas of the reform (liberation of business, private ownership on land, its free sale-purchase, reorganisation of collective enterprises, development of autonomous farms etc) were not embraced by the main bulk of households. Professional and administrative workers of agriculture also denied their support to rural transformation. A reform alien to people and not supported by leaders is doomed to flop!

The reformers missed their chance to make as much use as possible of the social potential that had been present in the society before the transformation. The high social price people had to pay for the reforms brought disappointment and doubts about their own wisdom.

The reformation of the agrarian sector was carried out according to traditional Soviet "technology", with its typical features such as directiveness, totality, enforcement and tokenism.

Another cause lay in the unpreparedness to work under the new economic conditions on the part of some managers. In our opinion, it is the body of directors that in the future should play the main role in the transformation of the Russian countryside. The practice has shown that economic managers demonstrate two types of economic behaviour: conservative-waiting and innovative-active. Here we can note a disparity between the mentality and behaviour of these managers. Very often, violent opponents (at a mental level) of the reforms demonstrate the standard market behaviour in real life.

And, on the contrary, "reform champions" (according to their self-assessments) in reality turn out mere onlookers of the innovative processes. The results of the activity of agricultural enterprises show that very few people can be successful under present conditions.

The state structures have themselves proved unprepared for the extreme scale and speed of the implemented reforms. This is seen in a lack of coherence in their implementation, constant changes introduced into the "rules of the game", and reckless removal of state regulation of the activity of the agrarian-industrial complex of the country.

Possible Ways Out of the Impasse

The Russian model of agrarian relations should, in our view, draw on the prevalent system of people's values and take into account the great importance attached by many of them to corporate solidarity. Even Western experts acknowledged as erroneous the Russian reformers' drive to root out people's "anticapitalist" mentality and their inability to change the common collectivist values into a creative power of reformation .11

What is needed is a reasonable combination of collective forms with private initiatives, an orientation to balanced development of the three segments of the agrarian economy with appropriate consideration of the trends emerging in their development. Special attention should be paid to successfully functioning part-time farms that create for themselves chances, on the one hand, to integrate in collective enterprises and, on the other, to be transformed into autonomous farms.

Market mechanisms that are being formed should be accompanied by state regulation of the activity of agribusiness and associated branches, especially so in the period of transition.

The rate, scale and depth of transformations should be brought into conformity with the presence in the society of social, economic and legal bases.

Special attention should be paid to the problems of the appearance of new economic agents able to work under emerging market-based conditions of economic and social risks.

For a deep and objective assessment of the agrarian reform it is necessary to provide for scientific monitoring of its progress on a national basis and in individual regions.

Notes

1. Kalugina, Z.I., Paradoxes of the Agrarian Reform in Russia. Sociological Analysis of Transformation Processes (Novosibirsk: IEIE SB RAS, 2000), 152 p. (in Russian).

2. Agriculture of Russia (1995) (Moscow: The RF Goskomstat 1995), pp.48-49.

3. Russian Statistical Yearbook (Moscow: The RF Goskomstat 1999), p. 351.

4. Khlystun, V., "To Stabilise the Operation of the Russian Agro-Industrial Complex", in Economics, Management 4 (APK, 1997), p.7 (3-16).

5. Russian Statistical Yearbook (Moscow: The RF Goskomstat 2000), p. 361.

6. Kalugina, Z.I., "Social Bounds to the Development of Autonomous Farm", in Izvestia SB AS of the USSR, series Region: Economics and Sociology, Issue 3, (1991), pp.35-42.

7. Russia in Figures (Moscow: The RF Goskomstat 2000), pp. 202, 211.

8. "Agriculture in Russia in 1996: Economic Review by the RF Goskomstat," in Economics, Management 3 (APK, 1997), pp. 3-10.

9. Rutskoy, A., and N. Radugin , "Agrarian Crisis Continues", in: Economics, Management 1 (APK, 1997), pp. 3-7.

10. Stroev, E., ed., The Conception of Russia's Agrarian Policy in 1997-2000 (Moscow: Open Company - "Peak - Club", 1997), 352 p.

11. Admiral, Peter "Where is Russia Moving?," in Problems of Management Theory and Practice 4 (1995), pp.8-13.