Zemfira I. Kalugina

PRIVATE FARMING IN RUSSIA: A THORNY PATH TO REVIVAL

In "Farming and Rural Systems Research and Extension. Local Identities and Globalisation". Florence, Italy, April 8, 2002. Fifth IFSA European Symposium, pp. 148-157.

Institute of Economics and Industrial Engineering Russian Academy of Sciences Siberian Branch. 17, Ac. Lavrentiev Prospect, 630090, Novosibirsk, Russia

Abstract: The paper focuses on revival of private sector in the Russian agrarian economy. Using statistics, by-law documents, field research data as well as personal observations the author analyses institutional framework, trends and current problems of private farms formation in the period of transition (1990-2001) and their share in the internal food market. A special part of analysis is devoted to prospects of the private sector, specifically, possible transformation of part-time household operations into independent full-time farms. In conclusion the author gives her own vision of the model of agrarian relations in Russia.

Problem background

The problem of efficient land owner is not new in Russia, it is enough to remember the history of the Russian state. In the serfdom period slavery could not provide efficient use of land. The tsarist government had to liberate peasants from personal dependence on landlords and let them keep their land allotments (for redemption payments). But no radical change in rural economic relations had occurred because part of peasants’ former lands (pastures, woods, meadows, commons for animals) and tools remained in the hands of nobility as well as certain levers of extra-economic pressure. Liberated but plundered peasants could not use land in reasonably efficient way. Restricted by collective responsibility and communal use of land, the “liberated” peasants never became real masters on land.

In the beginning of the XX century P.A. Stolypin, an outstanding politician , decided on radical land reform. Russian peasants were endowed the right to come out of the commune and organise independent peasant farms. The edicts of the government (credits on soft terms, land sales on low prices, subsidies for resettlement from overcrowded central regions to free lands in Siberia) permitted to avoid serious riots. The right of exit from commune was exercised by 2.5 million households in all, or by 24%, in 40 gubernias of European Russia (Liashenko, P.I. 1948: 266]. The peasant commune, however, was not completely destroyed, the major bulk of peasants were included in the system of communal use of land restricting their economic freedom. The death of the reformer and revolutionary transformations of 1917 prevented the reform from being properly accomplished.

In 1917-1918 land was nationalised and equally redistributed. Along with rural middle class, land was given to rural underclass who, for absence of required tools and other equipment, could not farm their allotments and, therefore, had either to rent them out to more wealthy peasants, or themselves to rent the necessary means of production. Overridden with poverty and illiterate, rural inhabitants could not raise agricultural performance. In growth rates the agrarian sector was far behind the unfolding industrialisation.

The 1921 X Congress of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) adopted a new economic policy. One of its key objectives was to overcome agrarian versus non-agrarian disparities through certain revival of market relations. The new policy led to economic redistribution of land among social groups of agrarian population. In this period rural middle class, rich minority (rural bourgeoisie) sharply increased and strengthened and the other part of rural population was marginalised and turned to hired labour in kulaks’ (private landholders’) farms.

In the early XX century there was a great rise in rural cooperation movement which within a short time became one of most advanced in the world. It started with the Stolypin reform and continued into the initial years of the Soviet power, notably in the period of new economic policy. Thus, as of January 1, 1924, agricultural cooperation of the RSFSR included 12 thous. agricultural and credit partnerships, 1.5 thousand dairies, 500 other types of agricultural cooperatives and about 11 thousand agricultural communes, that is, about 25 thousand cooperatives of all types. These cooperatives included about 1.5 million peasant households, mostly middle- and low-income ones (Chaianov, A.V. 1925).

But in the 1930s, after adoption and implementation of a policy at blanket forcible socialisation in agriculture, this process slowed. The huge group of free landholders was subject to physical destruction and transmission between generations of social experience of independent and efficient agricultural producer discontinued. This, of necessity, lowered labour productivity in agriculture and led to shortage of domestic food supply.

The establishment of state-collective agriculture had alienated the workers from land and means of production. Long-term (lasting) incentives were replaced by short-time ones with negative consequences for work motivation and public property. All attempts at changes to correct the situation made by the command system such as introduction of intra-organisational payments, subcontracts, intensive technologies failed to yield sustainable effects. They were effective only for a short spell of time and only in special model farms (“beacons”) that were put in advantageous conditions. Every next campaign would bring the situation to its former circles. The socialist administrative system was immune to market elements alien to it. For a real change in the situation radical reforms were required.

Institutional framework of private farming revival

The radical economic reform started in the early 1990s was to bring positive transformations to the Russian agrarian sector: land reform, reorganisation of collective and state farms, rise of private sector and unfolding rural inhabitants’ social activity and economic initiative. If assessed in terms of private sector formation, the agrarian reform surely has created the necessary legal basis for it.

The first is institutionalisation of new forms of economic activity, formation of mixed agrarian economy to promote free competition in agrarian market. Diversity of forms of economic activity makes it possible to use the advantages of both large and small production - the opportunities of large-scale operations and citizens’ initiatives.

The second is changes in ownership relations to provide redistribution of land and other resources so that finally they can reach efficient owners. In this way preconditions are created for rise of private sector and development of agrarian services and consumer facilities. The Land Reform Law passed in December 1990 repudiated the state monopoly on land on the whole national territory and installed private land ownership. This right is fixed in the Constitution of the Russian Federation.

The third is abolishment of administrative restraints on the size of household plots farmed in the rural side.

The fourth is declaration of expanded economic liberties. Primarily it is the right for members of former collective and state farms to choose that particular form of economic activity, which fits their interests, needs and opportunities supplemented with the right to leave the enterprise without a need to seek permission from the administration and remaining members.

The fifth is governmental support to farmers. At the initial stage, a fund of lands earlier in possession of collective enterprises was set up for their distribution among beginning farmers. The farmers were also allowed to rent additional lands from private persons or collective enterprises. In regions, they were provided with training and consulting facilities. At present, the government assigns to the emerging private agrarian sector loan and leasing resources and partially pays the credit interest.

The sixthly is endowment of each agricultural worker with shares of equipment and land to start up own business. This provided rural inhabitants with a certain initial capital.

Development of peasant autonomous farms

Since the adoption of the RF Law on Autonomous Farms and the reorganisation of collective and state farms, Russian peasants have acquired the real possibility of becoming independent economic agents. But in this period only a small part of them used the granted opportunities. Having been earlier many times cheated by the state, the Russian peasantry did not respond the urges to use private initiative with their mass withdrawal from the collective “penal camp”. And their strategy, as was shown later, was shrewd and fully justified. In practice the state was unable to assure the rights of private ownership, did not carry out a clear and consistent policy with regard to private sector and could not provide the enforcement of contracts made by all market participants.

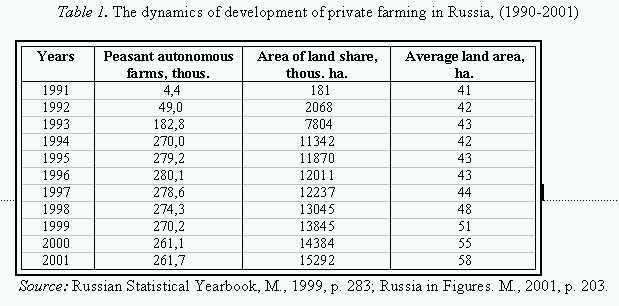

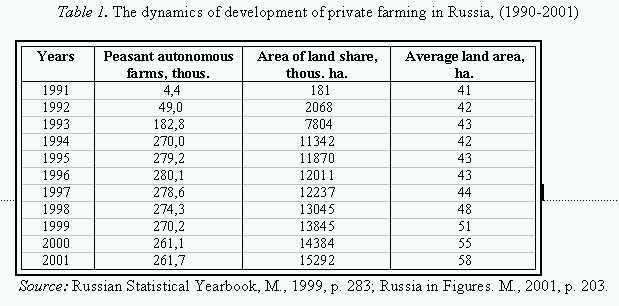

The dynamics of the number of autonomous peasant farms show that at the beginning of transition the country did possess a social base for development of the private sector as one of sectors of agrarian economy. From 1991-1996 their number increased to 280 thousand. But by 1994 the growth-rate had began to decrease. And this process of ruin and surrender is increasing. The number of farms that surrendered made in 1992 5.1 thousand, in 1993 19.1 thousand and in 1994 45.9 thousand. (The RF Goskomstat. 1995:53). Since 1997 the number of surrender for the first time exceeded the number of newly created farms (Table 1).

And the rates of their absolute reduction have been increasing up to 2001. While in 1997 the number of private autonomous farms over the previous year decreased by 1.5 thousand, in 1998 by 4.3 thousand, in 1999 by 4.1 thousand, and in 2000 by 9.1 thousand.

The studies conducted in the national regions show that the main causes for instability of autonomous farms are extremely high taxes, exorbitant prices of agricultural equipment, fuels and other resources, violations of the owner's rights, low subsidies from the state, allotment of lands of low quality and distanced from inner regions, and the lack of roads and communications. Our studies confirm these conclusions.

If all problems are grouped in large subgroups by level of their emergence and solution: global, local and individual (group-related), then we get the following picture. The most essential and often recurring in respondents’ replies are problems of governmental level, such as imperfection of tax legislation, disparities of prices, instability of state policy, lack of credit resources etc. (the summary percent 249). Next come problems appearing at local level. They are manifested primarily in opposition of local authorities and bureaucracy to enterprise development, in infringement of farmers’ rights to allotment of land plots of due quality situated not far from the village and communications, establishment of high rent payments for productive and trading premises (summary percentage 56). And, finally, problems caused by relations among social groups (sellers and consumers of goods and services, employers and employed, business partners and competitors: racket, unscrupulousness of partners, low skills and low commitment of employees (summary percentage 23). One of five farmers indicates low solvent demand of inhabitants which depends both on the policy of the state in the field of incomes and on the efforts of citizens themselves.

We realise that a part of the failure must be attributed to subjective causes, to the Russian peasants' lack of experience in independent economic activity, lack of knowledge, and an unpreparedness to work under economic and social risk.

Half rural businessmen do nothing to solve the emerging problems not believing they can do anything. As was put by one of them, “ everything takes its own course”, “somehow we manage to wriggle out”, “fulfil all that is required”. Only a small part of entrepreneurs appeal to different authorities for help in solution of problems they are confronted with.

In 2001 the number of autonomous peasant farms again increased by 600 units, and the area of lands granted to all of them increased by 908 thousand ha [3, p. 203]. As of January 1, 2001, there were 261.7 thousand autonomous farms with a land area of 15.3 million ha, 56 ha per farm. Agricultural lands make in them 13.5 million ha, including 9.8 million ha of arable lands. The autonomous farms account for 6.7% of national agricultural lands and 8.1% of arable [3. Pp.198, 203].

As a positive trend we should note the enlargement of autonomous farms. As was shown by special studies conducted by state statistical agencies in the Novosibirsk oblast in July 2000, the size of farms had an essential influence on their character and efficiency. While a small or middle-size farm accounted for 80.1 ha., 1.1 horned head, 0.5 cows, 1.6 pigs, 0.7 sheep and goats, 4.2 fowl, then the average large farm had 1017 ha and 16 large horned livestock, including 6 cows, 30 pigs, 3 sheep and goats, 21 fowl. The analysis has shown that with increased land use, the output, marketability and efficiency also increase [4].

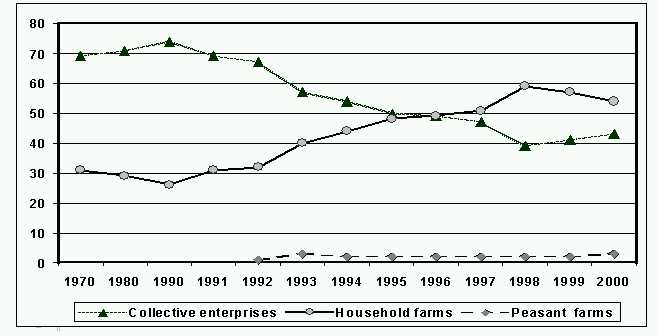

The proportion of autonomous farms in the total agricultural output is consistently low and does not exceed 3% (Fig. 1). But since 1995 some increase is witnessed in their share in production of corn – from 4.7% to 7.1%, sunflower seeds – from 12.3 to 12.6%, sugar beet – from 3.5 to 5.4%, meat (on hoof) – from 1.5 to 1.9%, and milk – from 1.5 to 1.8% [6, pp. 161, 162]. For all that, private farming has not become the dominant form in the rural side.

Back in 1991, when analysing necessary and real conditions for autonomous farms formation in the country, we arrived at the conclusion that blanket de-collectivisation was too rash. Considering the state of the public mind, the level of industrial potential, the condition of legislation, the features of the social-political situation in the country, and taking into account that for transition to a market economy much time was needed, we came to the conclusion that in the foreseeable future autonomous farms could not become a dominant form of agricultural production in the Russian countryside. It was only possible to speak with confidence about existing preconditions for establishment of a mixed agrarian economy, where autonomous farms would be one of its sectors [7]. These predictions were fulfilled. It should be noted that Russia does not differ from other former socialist countries, which have started transition to market economy.

Differentiation among Autonomous Peasant Farms

At present autonomous peasant farms are sharply differentiated. Noticeable are three types.

The first type are small subsistence farms with land parcels under 5 ha. They are very much like part-time household operations and satisfy the needs of the family. Their proportion in total autonomous farms is fairly high and makes at present nearly a fourth.

The second type are peasant single-family autonomous farms proper. The size of such farms does not exceed 100 ha. As a rule, they are worked by members of the peasant family and their relatives. Hired labour is taken only for peak periods in farming activity. The level of mechanisation is not high in them. It is not a rare case when several farms co-operate between themselves for spring field and harvesting operations. It is the most common type of peasant autonomous farms. They account for over 60% of farms.

The third type are large private agricultural enterprises of a commercial type. The area of agricultural lands in them is far above the average. Some of them work over 1000 ha. A substantial portion of this land is leased. The lessors are, as a rule, inhabitants of this village - pensioners, social sphere workers and others who after reorganisation were given shares of land. In the emerging land market these farms are becoming serious competitors to reorganised collective enterprises, which due to their poor financial standing not always can pay out dividends and their lessors can prefer a more reliable lessee. This, in turn, stimulates to more efficient use of land. Production in such farms is based on wage labour. The workers are hired for permanent or seasonal operations. Such farms, as a rule, are well equipped with modern agricultural machinery and transport vehicles. Their percentage is not high - about 12%.

In other words, differentiation of peasant farms shows that in land redistribution market mechanisms begin to act. This will certainly facilitate the formation of an efficient owner and a rational use of agricultural lands.

The social context for the emergence of private farming

Sociological surveys conducted in different national regions have shown very convincingly that in the beginning of the reforms the public had had the social base for development of all forms of rural business including the private farming. The disastrous situation of collective farms, growth of unemployment and drop of living standards promoted, in our view, rural inhabitants' orientation to entrepreneur activities too.

Pilot study of issues of rural enterprise conducted, with this author's participation, by the researchers of the Institute of Economics and Industrial Engineering, SB RAS, in 2000 in a district of the Novosibirsk oblast (N= 300rural inhabitants non-entrepreneurs and over 100 entrepreneurs with own business) has shown the existence of potential social base for rural business, including independent peasant farming. According to our data, over 30% of rural inhabitants would agree to start up own business or peasant private farming if they had starting capital (66% replies), lower taxes (23%), effective assurances (18%), accessible prices of production inputs (19%) and organisation of sales (17%).< /FONT>< /FONT>< /FONT>< /FONT>

By use of cluster analysis 2 subgroups of potential entrepreneurs were identified by the following criteria: education, material standing, experience in management. The members of the first subgroup had comparing to the second a lower level of education, material standing and no experience in management. These people mostly had skilled (66%) and unskilled (25%) worker backgrounds with complete or incomplete secondary schooling and elementary vocational technical training, 42% described themselves as poor and 58% as average well to do. The second subgroup of potential entrepreneurs with a higher entrepreneur potential made a fifth of all potential entrepreneurs. The members of this subgroup had a higher level of schooling and older age. About half of them (47%) occupied earlier high- or mid-level administrative positions, the other half were professionals. The proportion of young people under 30 years of age was here 42% against 62% in the first subgroup. By material possessions three fourths of this subgroup identified themselves as mid well to do, and a fourth as poor.

Hard opponents of private business who under no conditions would establish own business, including private farming, made about 40% of rural inhabitants. Main reasons for refusal to open own business are:

- high price of equipment and other inputs, high taxes - 38.2%,

- lack of starting capital - 27.2%,

- lack of experience in working independently, habit to work in a collective - 23.8%,

- absence of assurances - 12.9%,

- difficulties in running own business -12,4%.

About a fourth (24.3%) of this part of rural inhabitants are involuntary opponents of private entrepreneurship who, by personal reasons (old age, poor state of health, low schooling etc.) cannot undertake private business.

In general, it is possible to state that at present there is a sufficient enough social base for the development of rural enterprise. But the final decision to become or not become an entrepreneur will much depend on the state policy and on the way it will be carried out on the spot by local governments.

The analysis has shown that the real social base for the development of autonomous private farming is presented by highly educated rural inhabitants of middle age, mostly locals, most of whom (over 40%) earlier had an upward mobility, which is double the similar figure for the total array of the surveyed rural people. The autonomous farmers assess the level of their material standing as far above the average, although no one described it as high-income. The above-average level was reported only by one of ten farmers, over a half thought it average, a third, below average. Unjustifiably high taxes, inflation, low effective demand for agricultural products, unstable agrarian policy of the government impede private farmers from expansion of activity, and, accordingly, limit the farmers' opportunities to improve their material level.

Therefore, in general, farmers can be described as mid well-to-do group of rural inhabitants. And over a half (51%) farmers marked improvement in their material standing over the last year or two, 35% did not change their material status, 7,0% noted its deterioration. At the average, among rural inhabitants these indicators were 27, 40, and 31%, respectively.

Analysis of motivation to entrepreneur activity has shown that private farmers the key motives are desire to be independent, autonomous in economic sphere, opportunity to implement own plans, career ambitions, desire to be a success, realise one's plans. It is noticeable that about 4% of rural entrepreneurs indicated as a motive to entrepreneur activity a desire to follow the pursuit of their fathers. Studies conducted by western specialists show that an important role in the formation of the social base of enterprise is played a family member's earlier experience in business. In Russia the historical route of agricultural entrepreneurship was stopped in 1917, the numerous groups of rural independent commercial peasants were subjected to physical extermination. So no resurrection of private business had become possible until the 1980s when the laws on co-operatives and new Civil Code of the Russian Federation were adopted.

Part-time household farms and prospects of their transformation into autonomous full-time farms

Part-time household farming (LPH) is a specific segment of agrarian economy based on use of resources and the labour potential of rural families. Part-time farms as a specific form of production under socialism appeared by the end of the 1920s in the process of collectivisation of individual peasant farms when means of production, including land, became state property and families primarily employed in the public sector were entitled to individual part-time farming (without use of waged labour) on small household plots. In 1991 these plots were, under the Constitution of the Russian Federation, passed over to citizen ownership.

In the process of agrarian transformation and partial disintegration of collective farming, the protracted and complicated character of the establishment of new economic forms in the agro-business complex, the role of household farming as the most flexible, steady - enough and self-tuning organisational-legal form in agricultural production has increased. While in the public sector there has been a notable decline of agricultural output, in the households' part-time farms, on the contrary, it was increasing to make up in 2000 54% of total national output (Fig. 1).

Source:Russian Statistical Yearbook / The RF Goskomstat. - M., 1997, p.379; Russia in figures / The RF Goskomstat. - M., 2001, p. 199.

According to statistics, in 1999 15.5million families in Russia had household plots with total area of 6.1 million ha or 0. 40 ha per household. In addition to it, 14.1million households had land plots in collective gardens with total area of 1.3 million ha. or 0.09 ha per household. The collective kitchen gardens with total area of 0.44 million ha were used by 5.1 million households., or 0.085 ha per household. And 6.1million households held large cattle, 4.1 million had pigs, 3.0 million households held sheep and goats. As of 1 January 2000, households held 10.1 million heads of large cattle, 7.8 pigs and 9.1 sheep and goats combined [6, pp. 369, 362].

In 1994, 1997, 1998, however, there was a stabilisation or even reduction in the output of agricultural products on household farms. In our view, the emergent trend to a certain decline in the households' output is attributable to several reasons. One is a consequence after destruction of the production potential of collective enterprises the resources of which (fodder, seeds, agricultural equipment, transport vehicles etc.) were used by household farms under privileged conditions. The second point is that the financial possibilities of a rural family had substantially diminished in the result of lowered standard of living, including depreciation of savings. Point three is that the labour potential of a rural family has practically been exhausted. Analysis of time budgets of the rural population has shown that many families are running their part-time farms to the limit of their physical power.

At present, legislative and economic prerequisites have been created for the development of the part-time farm as an equal form of agricultural production and for its possible transformation into an autonomous farm.

First, the legislation has fixed the equality of all forms of agricultural production recognising the part-time farms of households as a rightful form of economy in the agrarian sector. And all work collectives and individuals are entitled to choose a preferable form of production in accordance with their wishes, opportunities and needs.

Second, all constraints on the number of animals held by a household have been removed.

Third, according to the current legislation, household land plots can be enhanced up to one ha by lands that are in the management of local councils. Apart from this, rural inhabitants who were given land shares (workers of agriculture, pensioners, and some categories of workers of the social sphere) are entitled to use them to expand their part-time farms.

And, lastly, according to the operative RF Constitution, land and other means of production can be privately owned.

Under these conditions rural households have a choice: either to work their household plots (LPH) in cooperation with other economic agents of the agro-industrial business using aid from collective enterprises, or to transform them into autonomous farms. The possibility of such a transformation is recognised by about 20% of rural respondents. The basis can be a large LPH of a commodity type to which about a fourth of rural families are oriented. But over a half of the rural families surveyed think that transformation of LPH to autonomous farms is impossible because, according to them, LPHs cannot do without aid from collective farms. The latter, even under difficult economic conditions, continue to give their workers different kinds of aid in the form of young animals, seeds, agricultural equipment and transport vehicles on soft terms or free of charge.

The assessments by experts (professional and administration workers of agriculture, number of respondents 566) the prospects of LPH transformation into independent farms are more pessimistic. No more than 2.9% of experts believe that LPH can be viewed as a transition to the autonomous private farm, while 61.2% believe that LPH can be successfully developed only in co-operation with collective enterprises. Moreover, at present, some private farmers ask their local administration to register their autonomous farms as household plots.

In our view, the perpetuation of LPHs in their former type is promoted by the existing order of taxation where household plots are practically exempt from income taxation because the land tax paid by LPH, due to its small amount, does not affect their profitability which is further substantially increased through the use (free or under privileged conditions) of the resources of collective enterprises. Such a position of LPH as a specific form of non-official agrarian economy is understood by most of the rural population and is reflected in their behaviour. Rural people understand that transformation of LPH from the non-formal sector of the economy to the formal one would involve a very hard pressure from taxation and the stopping of aid from collective enterprises.

The role of LPH in the process of the establishment of a private sector in the agrarian economy is controversial. Being developed in parallel with and, substantially, at the expense of resources and aid from collective enterprises, if perpetuated it would preserve the old system of economic relations. But, on the other hand, it helps the rural people to acquire skills of frugal and efficient management of land, and develops in them the social qualities required in a market economy such as business-like character, entrepreneurship, and independence. The characteristic features of LPH operators and their families are freedom of activity, independence in economic decision-making, and full economic responsibility for the results of their work. In other words, private part-time plots help shape economic agents of a new type.

Although at present most rural inhabitants do not dare to undertake the operation of an autonomous farm, current realities (decline of production in the public sector, very low wages in agriculture, irregular payments, increasing unemployment) enforce them to expand the scale and commodity quality of their part-time farms, which, by scale and function, are approaching the autonomous farms. And the former collective and state farmers are, as if involuntarily, becoming independent farmers.

So far, the latent processes going on in the contemporary Russian countryside have remained so far beyond the comprehension of the public, and thus need to be thoroughly researched. It is these processes, in our view, which can mould the trends and character of changes in the Russian countryside in the near- and mid-run.

Conclusions

The Russian model of agrarian relations should, in our view, draw on the prevalent system of people's values and take into account the great importance attached by many of them to corporate solidarity. Even Western experts acknowledged as erroneous the Russian reformers' drive to root out people's "anti-capitalist" mentality and their inability to change the common collectivist values into a creative power of reformation.

What is needed is a reasonable combination of collective forms with private initiatives, orientation to balanced development of the three segments of the agrarian economy with appropriate consideration of the trends emerging in their development. Special attention should be paid to successfully functioning household farms that create for themselves chances, on the one hand, to integrate in collective enterprises and, on the other, to be transformed into independent peasant farms.

Market mechanisms that are being formed should be accompanied by state regulation of the activity of agribusiness and associated branches, especially so in the period of transition.

The rate, scale and depth of transformations should be brought into conformity with the presence in the society of social, economic and legal bases.

Special attention should be paid to the problems of the appearance of new economic agents able to work under emerging market-based conditions of economic and social risks.

For a deep and objective assessment of the agrarian reform it is necessary to provide for scientific monitoring of its progress on a national basis and in individual regions.

References

1. Liashenko, P.I. The History of the National Economy of the USSR. M.: Politizdat, 1948.

2. Chaianov, A.V. A Short Course in Cooperation. M.: Cooperative Publishers, 1925.

3. Russia in Figures / The RF Goskomstat. - M., 2001.

4. Basic Indicators of Autonomous Peasant Farms Formation in the Novosibirsk Oblast. RF Goskomstat, Statistical Office of the Novosibirsk oblast. Novosibirsk, 2000.

5. Agriculture of Russia / The RF Goskomstat. - M., 1995.

6. Russia in Figures / The RF Goskomstat. - M., 2000.

7. Kalugina Z.I. "Social limits of autonomous peasant farms formation". Izvestia of the SB AS of the UUSR, 1991. Issue 3.