Zemfira I. Kalugina

Adaptation Strategies of Agricultural Enterprises

During Transformation" in Rural Reform in Post-Soviet Russia, eds David J.O'Brien and Stephen K.Wegren (Woodrow Wilson Center Press Washington, D.C., The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore and London, 2002), 367-384.

Introduction

The chapter is drawn from a survey of adaptation strategies of agricultural enterprises and families in an unstable environment conducted at the Department of Sociology, Institute of Economics and Industrial Engineering, Siberian Branch, Russian Academiy of Sciences, under my direction and with my participation in two rural districts of the Novosibirsk oblast in summer 1998. It is a case study of four agricultural enterprises aimed at examining different patterns of adaptation. The data were collected through unstructured and focused interviews with enterprise managers and specialists (N=60), questionnaire survey of employees (N= 404), and analysis of statistics from 1992 to 1998 (the period of radical economic reforms), and related documents1.

The project’s primary objective was to compare adaptation strategies used by economically strong and economically weak agricultural enterprises. The comparative analysis included measuring the effect these stratigies on the economic behavior of workers and their families in primary and secondary sectors of the economy, and assessment of economic results and social costs.

Adaptation strategies were analyzed along three dimensions: economic, social welfare, and labor. Economic strategies included choice of organizational-legal status, extent of output diversification, innovation policy, development of processing facilities and non-agricultural businesses, access to nonfarm emploement, and policy regarding part-time and commercial farmers. Social welfare policy was assessed by two criteria: development of social infrastructure and maintenance of employees’ living standards. Labor policy was evaluated by changes in the number of employees, the unemploement rate, financial and material support of young families (e.g., payment of educational fees), and opportunities for skill upgrading and education.

There were five specific goals of the approach just described: (1) examine special features in the enterprises’ economic, social and labor policies and assess objective and subjective factors in economic growth and social stability; (2) analyze how the different adaptation strategies affected the conditions and opportunities for employees to actualize their labor potential; (3) assess social costs of a given strategy that were borne by the enterprise, its employees, and their families; (4) assess the degree of social tension among personnel as well as employees’ involvement in or alienation from the enterprise; and (5) examine forms, means, and outcomes of employees’ and their families’ adaptation behavior geared to maintaining and improving their living conditions, offset social costs, and provide for the family’s future.

Novosibirsk Oblast

Novosibirsk oblast is located in southwestern Siberia. The western Siberian region includes seven federal geopolitical units: the Altai krai, Republic of Altai, and the Novosibirsk, Omsk, Kemerovo, Tiumen and Tomsk oblasts. Novosibirsk oblast covers an area of 178.2 squere kilometers and contains a population 2,745,800. Population density, as of 1 January 1998, 15.4 persons per squere kilometer. The distance from Novosibirsk to Moscow is 3,191 kilometers. Map 15.1 shows the location of Novosibirsk oblast.

Map 15.1

Novosibirsk oblast

The entire western Siberian region, including the Novosibirsk oblast, is in a zone of "risky " agriculture. Nonetheless, this region has a stable and rather high share - 2.3 percent in 1997 -in the national agricultural output2. Principal products include grain, potatoes, and vegetables, as well as meat and dairy. Poultry products, honey, flax, and food processing also play important roles in the oblast's economy.

Monitoring the progress of the agrarian reformation in Siberia (one of the test fields is Novosibirsk oblast) leads to the conclusion that the state of the agrarian sector of the region is determined mainly by general national rather than local factors. A comparative analysis of survey findings in Siberia with other regions of the country shows the basic similarities in the processes underway in the agrarian sector throughout the country.

Conditions in the Russian Agrarian Sector Before Reform

In the 1980s domestic agricultural production was not sufficient to provide a balanced diet to the Russian Population. In many areas, food distribution was rationed. Attempts to improve the situation in the bureaucratic-administrative command system involved superficial adjustments turned out futile in the long run. These incremental adjustments, such as intrafarm cost-benefit analyses, various types of contracts, and capital-intensive technologies, did not affect core problems. These efforts resulted in short-lived improvements and then only within specially chosen experimental farms that were artificially created and enjoyed more favorable conditions than elsewhere. After each "reform" campaign, everything returned to its previous condition. The socialist system repulsed the market elements alien to it. For the situation to be reversed radical reforms were needed.

Reorganisation of Collective Agricultural Enterprises

The reorganisation of collective and state farms was completed in 1994. Almost two-thirds (66 percent) of these large enterprises changed their organisational-legal status, while others retained the traditionalcollective organizational form. A total of 300 of the large enterprisesregistered as open joint stock companies, 11,500 as partnerships (of all types), 1,900 as agricultural cooperatives, 400 as farms affiliated with industrial enterprises or the other organizations, 900 as associations of autonomous farms, and 2,300 as other forms of agricultural organozation. Among sovkhozy, 3,600 retained their traditional form, as did 6,000 of the kolkhozy. By forms of ownership, agricultural enterprises were distributed as follows: state ownership 26.6 percent, municipal ownership, 1.5 percent, private ownership 66.8 percent, and mixed ownership, 5.1 percent.3

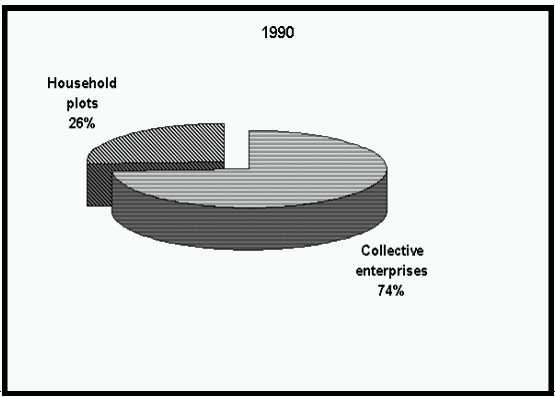

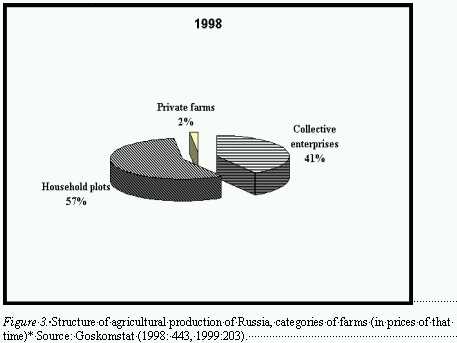

The reorganisation of collective enterprises was supposed to be the first step toward the creation of a mixed agrarian economy based on equality of all forms of ownership and land management. Reorganisation did not, however, result in higher efficiency and higher output for these large-scale collective enterprises. Agricultural output and the share of national agricultural production from these enterprises have been in steady decline. In 1990, the large-scale collective agricultural enterprises accounted for 74 percent of total output in Russian agriculture, but by 1998 they only accounted for 41 percent ( see Figure 15.1). A livestock herd in the large enterprises continues to decline. Most of these enterprises are in a critical economic position. Average profitability of these enterprises at the end of 1991 was 43 percent, declining to - 2 percent in 1995 and - 20.5 percent in 1996.4

V. Khlystun, a former minister of agriculture and Food of the Russian Federation, explains the unprofitable situation in the Russian agriculture as the result of several factors, including the constantly increasing disparity between agricultural products prices and input prices; extremely low state subsides, delays in the settlement of the accounts receivable; and monopoly markets in agroindustry enterprises and organisations, such as processing, and diverse goods and services.

*

The net result of reforms has been to replace an inefficient state sector of the economy with innefficient private sector. The number of inefficient and unprofitable enterprises that have no working capital of their own and to whom bank loans proved inaccessible (due to high interest rates) was 96 in 1995, 137 in 1996, 138 in 1997, and 142 in 1998.6

In my view, the underlying cause of the falure of reform efforts was the formal character of the transformations. The organisation-legal status of collective and state farms was changed but in essence the social organization of economic relationships remained the same.

Because most workers have not observed and difference between their previous status as employed workers and the present one as co-owners, there has been no change in their work motivation or behavioural patterns. In the Russian Federation president's message to the Federal Assembly of 1997 it was noted that "the established mutual rights and responsibilities between owners (stockholders) and managers (directors) were not observed. Directors often merely pushed the stockholders, even major ones, aside when making important decisions in matters that were precisely within owners' competence". The president's message asserted that stockholders' rights, a clear definition of rights and responsibilities of stockholders and managers, and the perfection of a mechanism of corporate management were priority tasks for the government upon which the course of the reform in 1997 depended.

The formal-legal and market mechanisms by which peasants can exercise their rights of ownership to their shares of land and other assets is not yet operational. In our surveys in Novosibirsk oblast, over 80 percent of the respondents had recived no dividends for their shares of asset and land that they had handed over to the large-scale agricultural enterprises for use. Most enterprises are unable to pay dividends to their workers. This situation is typical of other regions of the country as well.7

The paradox of the reforms is that instead of developing in people market mentality and behaviour, they are fact destroyng work motivation in the large enterprises. The most vivid example of this is the gap between workers' expectations at higher earnings and the declining ability of agricultural enterprises to reward workers' contributions. Today agricultural workers wages are less 40 percent of the national average, the lowest among all categories of workers in Russia. Wages are below subsistence level and typically paid several months late. Most important, the link between lewels and work productivity and worker qualifications has been destroyed.

One-third of rural workers said that the amount of their remuneration was not contingent on the efficiency of the large enterprise in which they worced. Employment in the public sector has now ceased to be a primary source of incomes for rural workers. In our 1997 survey of the rural population (n= 553),only 38 percent of respondents said that their wages were the primary source of their livelihood. Part-time farming was listed as the primary source of income for 42 percent of the sample. See also chapter 14 by O'Brien in this book.< /FONT>< /FONT>

In addition, opportunities for the large agricultural enterprises to use ther own resources to solve the social problems of their workers have been drastically decreased. Before reform many social-welfare benefits in rural villages, such as free housing, preschool or child care for children, and health care, were contingent on having a job in the large enterprise. After reorganisation, the collective and state farms were allowed to transfer the provision of social and cultural services to local governments. The latter, howevere, lacked sufficient financial resources and appropriate infrastructure to provide these services. This has led to a substantial decline of social services provision in the countryside. See also chapter 9 by Gambold Miller in this book.

These processes are at the core of a sharply decreased motivation to professional, high-quality and effective work in the large enterprises, as well as a drastic drop of the prestige of work in the public sector, especially so among rural youth. In our 1997 survey, 31.9 percent of rural inhabitants said they would prefer not to work at all, if unemployment relief could provide for a fairly decent standard of living. Only three years earlier, only 10.6 percent of respondents would have preffered not to work in similar circumstances.

Other responses indicate attitudes toward work. Over half (65.8 percent) of the respondents indicated preference for a small but guaranteed income. Only 28.9 percent of those surveyed would accept higher risk in exchange for high earnings. This current situation, in wich work behavior is effectively disconnected with remuneration, encourages people to gradually lose their self-confidence and to become accustomed state paternalism.

According to a survey (n= 735) inMay 1998, however, managers of large enterprises believe that a different set of factors were responsible for their low productivity: buyers’ insolvency (9 percent), shortage of finances (12 percent), high interest rates on loans (8 percent), increased share of imported foods in the domestic market (5 percent), high taxes (12 percent), instability of taxation and constant channges introducedl into the "rules of the game" (9 percent), low product prices (14 percent), lack of working capital (7 percent), weak enterprise managers’ powers and rights (3 percent), deterioration of the material technological base (13 percent), and impoverishment of natural resources (8 percent).8 < /FONT> < /FONT>

Nevertheles, there are some large agricultural enterprises in each province that are successfully functioning under the current unfavourable conditions. These farms have managed to quickly adjust to the new economic conditions. They have studied the market situation; identified the most profitable channels to sell their products; restructured their production according to market requirements; and successfully developed processing ventures and sell their products through their own network of shops, existing retail markets or trusted wholesale agents. Some of these enterprises have become founders of large commercial structures and have set up modern agroindustrial companies.

Economic Strategies and Forms of Adaptation by Enterprises and Families

A distinctive feature of the present transition period for Russian enterprises and households is that concurrently with the appearance of new institutions, new processes, new social phenomena, renovation of the existing institutions is also under way. Such adaptation has included «response to innovations», as well as «response to transformation».9 Adaptation can also be a response to change (novelty or alteration) occurring in the internal structure of the adapting person.10 After the period of sweeping reorganization of agricultural enterprises from 1992 to 1994, it is very important to know how economic agents have adapted themselves to their new status, functions, and roles. In our study, the adapting persons are agricultural enterprises and rural households. The economic strategies of enterprises can be viewed as a way of adaptation to the radically changing socioeconomic environment.

Our research has identified four different models of economic adaptation that have been used by agricultural enterprises and households in the current unstable envirinment.

Model 1. Active market strategy: productive and innovative adaptation of enterprises; orientation of most families to improving or maintaining their present standard of living.

The characteristic feature of this economic strategy is an active innovative policy, wich includes the introduction of advanced technologies, cooperation with domestic research and extension activities, cooperation with foreign firms, development of processing and storage facilities, effective schemes of work incentives, and a high level organization of primary and auxiliary activities. The latter include repair of farm equipment and steady links with business partners to develop reliable markets for agricultural products.

The enterprise’s adaptation is productive and innovative, based on the search and implementation of new ways of interacting with the environment. This type of adaptation is characterized by clearly defined objectives and use of new efficient methods. The accomplishments of these enterprises, found throughout Russia, were summarized above. Such enterprises, however, account for no more than 5 percent to 7 percent of all large agricultural enterprises in Russia. 11

Under this adaptation strategy, the focus of social welfare policy is to maintain and develop rural social infrastructure, aid to shareholders and employees with their part-time farming, organize summer vacation activities for children, and improve the landscape in the village community. Labor policy includes the retention of employees (in the 1992-98 period, worker numbers in the case-study farm increased by 11), the development a labor contract system, regular cash payments of wages, incentives for high levels of work performance, economizing of input resources, and punitive dismissal for breachers of discipline. The latter has a special significance. The loss of a job is not only loss of wages, but also loss of access to resources necessary for private farming. These resources are obtained by workers either in kind (grain, hay, young animals and so on) or at discounted prices. In addition, machinery operators have at their disposal agricultural equipment and transport vehicles which they use to render paid services for pay . In recent study of adaptation models used in Siberia, Fadeeva wrote: «The greater the difference between the total sum of goods and services obtained directly or indirectly by the job holder from his enterprise and his «nominal» wage in the payroll sheet, the more «valuable» is this job». 12

Enterprises adopting this strategy have paid the tuition for villagers in institutions of higher education. In addition, these enterprises have organized business travel abroad for their employees. Young men returning home from military service are given a sum of money equal to five times the minimum wage. The chairperson of the case-study company regularly advised young people to purchase shares in their company. Retirees were given from 3,000 to 7,000 rubles (roughly between one and two years' wages).

The case study enterprise's economic performance was quite good overall. The higher efficiency of production (40 percent) in accounts receivables exceeding accounts payable was the result of the realization of the active market strategy and innovative adaptation of this enterprise. In the 1992-98 period following the introduction of reforms, arable land usage declined only slightly, and livestock herds declined by 20 percent (including a 10 percent reduction of the cattle herd). Livestock herd reduction at the oblast level was much higher.

Typical opinions of the managers and specialists in enterprises using this type of adaptation strategy are as follows:

Our company «prospers» only in comparison with other companies.

If the subsidy going away from the country for «Bush’s legs» [refers to chicken legs imported from the United

States]

were given to our agriculture, it could really prosper.

Dividends - we don’t speak of dividends! We would be satisfied at least to keep production and pay minimum

wages. And pay taxes in due time not to destroy the enterprise.

When I was in France I paid 400 francs for shoes, while meat cost there 80-100 francs for one kilogram. So I

had shoes for four kilograms of meat, when at home I would have to pay the price of a whole suckling pig for

these shoes.

You see the disparity; what use is it to talk about prospects for the countryside!

The dominant strategies of families working in this type of enterprise were to improve or maintain their present standart of living (26 percent and 49 percent of families, respectively) through small-scale commercial farming (76 percent of the workers had small- scale household enterprises) and secondary paid job (35.5 percent of respondents would like to have secondary employment). Over 60 percent of the persons interviewed in this type of enterprise preferred to work overtime on their primary job to increase their incomes. Regular payments, even if they were modest, plus cash income from household commercial enterprises provided people working in this type of large enterprise with an acceptable living. Over a fourth of respondents were quite satisfied with their standard of living.

Model 2: Conformity economic strategy : compensatory adaptation of enterprise; most families’ strategies are aimed at maintaining the present standard of living.

Typically, large enterprises that have adopted this strategy are found in Soviet-era state farms specialized in meat and dairy and grain production that have been reorganized into closed joint stock companies. These farms' specializations have not changed, but they have built milk cooling and pasteurizing facilities in partnership with processing enterprises. The reorganization of collective and state farms was aimed at changing the organizational-legal status of collective enterprises, giving workers a right to free choice of forms of entrepreneurship. There were plans to diversify dairy processing, including sour milk products (sour cream, yogurt, and cheese). In the case-study enterprise, the mill built next to the grain-collecting station was used on a sharing basis. Grain was stored for a fee in grain-collecting stations managed by the company. When an enterprise pays a certain amount of money or other resources (a share) for the building of some facility (in this case, a mill) then it becomes a co-owner and can accordingly pay lower prices for the services of this facility (the mail).

These enterprises have steady partners in marketing and processing, but they believe that setting up their own retail trade enterprise would be more profitable. To this end, a retail store was being built in the district seat of the case-study enterprise. A construction shop was also available and in addition to doing jobs for the large enterprise, it supplied services to village residents for a fee. The company also opened its own bakery.

The type of adaptation in this large enterprise is compensatory,13 a combination of traditional primary agricultural production with partnership-or cooperative-based agricultural processing. The combination of primary and secondary activities allows these enterprises to more effectively market their commodities, obtain cash, and obtain higher profits. This mode of adaptation ensures steady growth under difficult economic conditions. We estimated that enterprises using this mode of adaptation account for 10 percent to 15 percent of large agricultural enterprises in Russia.

A large enterprise employing this adaptation strategy has a social-welfare policy that includes building a health-care rest home for the elderly and all workers in this enterprise; and providing infrastructure and services such as shops, schools, communications, and health care.

In the case-study enterprise, social-welfare sector workers have passed over their land shares to the company by contract. Working employee-shareholders and pensioners are assisted in part-time farming with hay, grain, other types of animal fodder, and young animals in return for their work (livestock growers are given calves as part of their work remuneraton). Every quarter each employee-shareholder is given 15 to 20 metric centners (one centner equals one-tenth of a metric ton) of grain free of charge. Other employees buy grain at discounted prices. Shareholders are provided with 20 to 30 centners of hay, and an unlimited quantity of straw for their privately owned livestock. During the harvest, equipment operators are provided with food at discounted prices. Needy households are allowed to take foodstuffs from shops on credit against wages. The most acute problem is housing construction.

The labor policy of this company can be summarized as avoiding mass dismissal. The number of company employees has actually increased slightly, primarily via accepting forced migrant from former Soviet republics. Young shareholders starting households were given a one-time cash benefit, and they were assisted in starting their own part-time farm. Secondary school and higher education graduates were given jobs.

The profit margin of this company was 11 percent. Receivables were five times greater than payables. Payments to enterprise partners for supplied products were perpetually in arrears, which greatly undermined the company’s ability to obtain loans. In the 1992-98 period, agricultural land area increased by 300 hectares, and the livestock herd declined by 30 (including a 35-percent reduction in the cattle herd, while the number of pigs increased). Livestock productivity has improved; for instance, between 1997 and 1998, the average milk yield per cow increase from 3,490 to 4,000 kilograms. The number of tractors decreased by seven. New equipment was not available. This problem was solved by purchasing second-hand equipment or repairing existing equipment by using parts from old equipment. These purchases were made primarily from private farmers who went out of business. In general, this type of enterprise has managed to maintain its position. The case-study company had plans to expand production, and to improve grain yields and cattle productivity.

Typical opinions of officials and specialists in this type of company are as follows:

Our innovations? First, this involves general attempts, ranging from director to rank-and-file worker, to economize

material inputs.

We are fighting small thefts that still are practiced, but the scale of these thefts is quite moderate.

Requirements for workers are very strict and discipline has improved.

At our meetings we keep persuading people that they are owners, shareholders. But it is not easy to awaken this

feeling.

With support from the company, a man can gain maximum profit from his own part-time farm too.

Before the reform we had 3,000 liters of milk per cow yield. The state farm was a millionaire. Many workers

could purchase individual cars. It was prosperity then. And they could provide education for their children… Now

we work harder but live 10 times worse.

At present, the work is very exciting, but it is very difficult too. Now it is self-reliance, how skillful you are, that

determines what you will gain. It is beautiful!

The prevailing family strategy in this type of enterprise is to maintain the present standard of living. Half of the workers interviewed said they would like to have a paid secondary job or to work overtime for extra income. About half of the families earned additional cash from sales of products from household plots.

Model 3. Mimicry economic strategy: deprivation adaptation of enterprise; orientation of families to survival or maintenance of the present living level.

The mimicry economic strategy is characterized by low innovative activity. Its typical features are low diversification of production, low development of processing facilities and no nonagricultural business. According to the enterprises' specialists, diversification opportunities have been missed. In their view, processing ventures and new production facilities should have been started six to seven years earlier. Lack of funds and difficulties in getting loans hindered planning for the development of new productions and processing facilities. Commercial loans could not be repaid because agricultural product prices were lower than input costs. In the case-study enterprise, a dairy that had been under construction for four years was abandoned due to lack of funds. This company had opened a small bakery, and a small woodworking shop employed two persons.

In this model, economic strategy is directed more at survival than growth. This strategy is characteristic of more than half of the enterprises in our study.

The social welfare policy associated with this economic strategy has been to preserve the entire traditional social infrastructure, including the music school, kindergarten, and the House of Culture, but housing construction was practically at a standstill. The situation in small villages was much worse. In some villages the school, the club house, and shop were closed. In cases of urgent need, workers were given cash loans at a 10-percent interest rate. The loan of 1,000 to 3,000 rubles was usually taken for 12 months or 18 months. Typically, the money was spent on nondurable consumer goods instead of durable goods. If wages were delayed (often for 2 months), workers took goods from the village shop against future wage payments.

In the case-study enterprise using this adaptive strategy, the average number of workers on the payroll was reduced by 27 persons from 1992 to 1998. According to the specialists, one of the reasons for employee turnover is an expanding urban-rural gap. The average monthly wage in 1997 was 498 rubles, which is below the subsistence minimum. As a result, the majority of rural residents maintain small household plots, and thus take on a large amount of manual labor. Young people, seek either to leave this environment or to find a nonagricultural job in the local labor market. The company could perhaps attract them by new housing but home construction was not financially viable. Although workers’ skills were generally satisfactory, constant skill upgrading is necessary. If workers do not leave home to upgrade skills or to meet with counterparts to exchange ideas and experiences, it is very difficult for them to maintain their skills at an adequate professional level. Specialists' skills were also becoming dated because most courses now must be paid for and the company could not afford to pay for employees’ transportation to take courses.

The financial standing of companies employing this adaptation strategy is not good. According to their specialists, 80 percent to 100 percent of vehicles and equipment were worn out. In the case-study enterprise, the number of tractors decreased by five, and combines by three over the 1992-98 period. The last purchase of new equipment was five to seven years ago. Purchased equipment is second-hand and obtained with credit. The livestock herd, including cattle, declined by about a third, and productivity dropped by about a fourth. Cultivated area did not change. Profitability over the period of the study (1992-98) fell by one-third. In 1998, payables were 15 times higher than receivables. The company recorded a 3,000-ruble loss in 1997.

Typical opinions of officials and specialists in farms using this type of adaptation strategy included:

No liberalization has occurred in the countryside. Everything has remained as it was in the past - one administrator,

several specialists. All power is with the enterprise director, employees are under the director’s authority and

guidance. While nearby state farms are ruined, ours is still functioning. The director makes every effort not to let

the enterprise be ruined and let people live in peace, be employed, be socially protected, and have high earnings.

The dominant strategies of those working in enterprises of this type were aimed at simple survival or maintaining the present standard of living (40 percent and 42 percent of families, respectively). Only 16 percent of the families seek to raise their living standard by farming household plots and a secondary paid job.

Model 4. Passive, biding-time economic strategy: destructive adaptation (disadaptation) of the enterprise and family survival strategy.

Typical features of this economic strategy include the reorganization of the enterprise into a closed joint-stock company, passive biding of time and hoping for changes and aid from the top, total depreciation of fixed capital, absence of processing facilities or steady ties with retail or wholesale markets, and little diversification of production. Prior to the reforms, the case-study enterprise specialized in poultry production, and then switched to grain and meat and dairy production. The enterprise switched its specialization after reorganization; this production diversification was forced upon it.

This strategy indicates that the enterprise has been unable to find its niche in the new economic environment, which has led to disintegration of the workforce and financial ruin. In other words, this strategy is tantamount to «destructive adaptation». This situation characterizes, in our estimation, about 20 percent of all large agricultural enterprises.

The social welfare policy of this type of company is aimed mainly at giving help to employees and pensioners to farm their household plots, rendering services to residents at discount prices, and assisting with transportation problems and health-care facilities. The paucity of resources available to deal with social problems intensifies social tensions among workers.

In the case-study enterprise, labor policy from 1992 to 1998 included a reduction of employees by a factor of 2.3. Regular wages had not been paid for a long time. The financial standing of the enterprise was not good. The livestock herd had declined by 75 percent, including a 70-percent reduction of the cattle herd. Livestock productivity has declined; for instance, average milk yield per cow in 1998 was only 1,628 liters, which was below the oblast average. The number of tractors declined in the case-study enterprise during this period by 104, and combines by 38. Payables exceeded receivables by more than 200 percent.

Opinions of officials and specialists follows:

There's no help from anywhere, we are no one’s concern.

No ideas, no innovations.

All has been ruined, equipment destroyed.

The only young people who come are odd persons, undisciplined, drinkers, those whom nobody needs.

Workers are stealing all things of whatever use, pilfer unused buildings, fodder, equipment – everything.

People live according to the old understanding – that it is not mine but everyone’s.

It is a deadlock.

The result of this mode of adaptation was that employees barely subsist. Over 70 percent of them reported deterioration in their living standard over the past two years. The chief source of income was small household plots, which greatly increased employees' work load. Forty percent of the respondents reported that they work to exhaustion Domestic strategies, including illegal actions, were oriented mostly to survival. The vast majority (89 percent) of the respondents excused this behavior, either in full or in part, by saying that they had no other choices. And about half of the workers attributed their disastrous situation to the poor financial standing of the company. Half of the employees could not recall any happy event in their life over the past year, and another 5 percent said that the past year had brought them only troubles. These families survived mainly on their small household plots, which account for up to 77 percent of their income. Most respondents expressed a willingness to take an additional paid job.

Conclusions

Notwithstanding the similarity of external conditions, the reorganized agricultural enterprises demonstrate drastically different models of economic strategies and adaptation to new socioeconomic conditions.

The choice of and results of a particular adaptation strategy were largely determined by the personality of the enterprise manager. This study has shown that the most successful enterprises did not change leadership during the period of reorganization. The most successful companies were those headed by so-called «red» directors who ideologically did not approve of the reforms but in practice demonstrated market models of economic behavior. In contrast, young directors, while embracing and supporting the ongoing transformations, did not possess adequate real-world experience and found themselves helpless in face of the difficulties in the present economic environment.

Rural people now understand the role of the leader. Forty percent of those surveyed believed that the lack of skills and erroneous actions of the leaders caused the deterioration in the economic situation of the enterprise. About the same share of rural respondents attributed their troubles to the erroneous course of reforms, ill-conceived state policies with regard to the agrarian sector, and a faulty tax system. Workers' hopes for their enterprise were associated with changes in the government's agrarian, tax and financial-credit policies and with the replacement of their enterprise manager. One of five employees believed that improving work motivations of rural people and improving work discipline are necessary. It is revealing that only 2 percent of the respondents hoped for a return to the former system and less than 1 percent thought that their enterprises could not be revived at all.

After reorganization, the economic situation of all agricultural enterprises deteriorated. But those enterprises specializing in production that was profitable under current market conditions were in better financial positions compared to others.

The economic situation of the enterprise at the beginning of the reforms had an impact on its process of reorganization and adaptation to new conditions, but was not always the decisive factor in causing its current financial situation.

The principal factors accounting for enterprises survival very diversification of production, a moderate innovation policy, and development of small processing facilities. The development of processing ventures was motivated by the desire of agricultural enterprises to achieve three goals. The first was to counter the pressure of large processing monopolies that dictate conditions to farm enterprises but do not always fulfill their obligations. The second was to ensure a small but secure source of cash. The third was to improve the profitability of processing ventures through the removal of middlemen.

Most large collective enterprises have no reliable channels for marketing their commodities. In the agricultural market, conditions are often dictated by wholesale dealers, racketeers, and criminals. Barter transactions make up a significant portion of transactions. In the Novosibirsk oblast, barter accounted for 2 percent of all grain transactions in 1992 compared to 22 percent in 1998.

Lack of credit to replace and maintain agricultural equipment, and to purchase fertilizers, veterinary products, and other inputs led to falling productivity.

There were no mechanisms for regular skill upgrading of workers and specialists. Higher costs for education and a higher cost of living, in general, made it increasingly difficult for young people in rural areas to get secondary or post-secondary professional education in the city. The situation was exacerbated by the absence of opportunities for exchanging experiences and contacts among professionals and skilled workers.

The price disparity between agricultural and industrial products, as well as higher energy prices, increases the unprofitability of agriculture. In turn, this has led to a contraction of social welfare programs and housing construction. These conditions increase social tensions and conflicts in large farm enterprises. Nevertheless, enterprises still manage to provide many social services to workers to assist them in small-scale private farming activities, thereby helping to maintain their standard of living.

The adaptation strategies used by large agricultural enterprises have had a major impact on dominant family strategies. The major means of survival of rural families were small-scale, part-time farming, secondary paid jobs, and illegal practices. In economically strong enterprises, most families were oriented to material affluence or maintenance of the present standard of living, while in economically weak enterprises, families were oriented only to subsistence.

Notes

1. The study was funded by the Russian Humanitarian Scientific Foundation, Project N 99N 99-03-00170.

2. Regiony Rossii (Moscow: Goskomstat, 1998), 432.

3. Sel'skoe khoziaistvo Rossii (Moscow: Goskomstat, 1995), 48-49.

4. Ye. Stroev, ed., Konceptsiia agrarnoi politiki Rossii v 1997-2000 godax (Mocow: Vershina Club, 1997), 343.

5. V. Khlystun, "Stabilizirovat rabotu agropromyshlenogo compleksa Rossii," APK: ekonomika, upravlenie, no. 4 (April 1997): 7.

6. Rossia v tsifrakh 1998 (Moscow: Goskomstat, 1998), 319.

7. G.M. Orlov and V.I.Uvarov, "Sela i Rossiiskiye reformy," Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniia 5 (May 1997): 43-53.

8. Rossiiskii statisticheskii ezhegodnik 1998 (Moscow: Goskomstat, 1998), 502.

9. G. Underwood, " Categories of Adaptation", Evolution, 8 (fall 1954): 372.

10. L. Korel, Sotsiologiia adaptatsii: etudy apologii (Novosibirsk: IEIE SB RAS, 1997), 40-113.

11. B. Poshkus, " Vnutrennie rezervy APK Rossii," APK: ekonomika, upravlenie 3 (March 1997): 14.

12. O.P.Fadeyeva, "Sibirskoe selo: alternativnye modeli adaptazii," in Krestianovedenie, teoria, istoria, sovremennost, eds. V.Danilov and T.Shanin (Moscow: MVShSEN, 1999), 227-240.

13. G.I. Tsaregorodsky ed., Philosophic Issues of Adaptation Theory (M.: Mysl, 1975), 177.